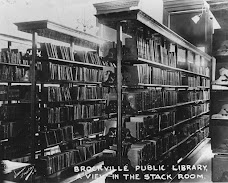

Library Service for Canada: A Brief Prepared by the Canadian Library Council, as Forwarded August 2, 1944, to the House of Commons Special Committee on Reconstruction and Re-Establishment. 10 leaves, 2 appendices [Ottawa?]: Canadian Library Council, July 1944.

In 1942, the Canadian House of Commons appointed a Special Committee on Reconstruction and Re-establishment. James Gray Turgeon, a Liberal politician from British Columbia, served as chair. The committee’s purpose was to study and report the potential problems and ensuing responses that might arise from a postwar period of reconstruction and re-establishment following the Second World War. The committee submitted a report of its activities and associated briefs in 1944 and completed its work in 1945. A major aspect of the committee’s activities concerned the state of culture across the Dominion. A variety of arts and cultural groups made submissions which helped create a better awareness of cultural issues. These early efforts provided a basis for which later developments could occur, which saw the federal government support Canadian artists and develop national institutions in the 1950s. In terms of library service, the Canadian Library Council (CLC) assumed the responsibility for drafting a brief earlier in the summer of 1944, but final approval was delayed until July. The CLC then forwarded its report to the committee for its 2 August 1944 meeting; however, the Council did not make an oral submission and receive questions, although references to the CLC’s proposal appear in the committee’s minutes for this date.

It was well known from many reports in the 1930s that library services in schools, colleges, and municipal institutions were deficient. A 1943 survey by the Canada and Newfoundland Education Association especially lamented the poor state of school and public libraries. One of its reported recommendations concluded: “That library service be extended over the whole Dominion. Not less than $1,000,000 per annum is required for this purpose.” The CLC, formed in 1941 and incorporated in late 1943, existed to promote library service and librarianship in Canada. It included representatives from library associations in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, the Maritimes, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan. By 1944, its membership was busy publishing information to raise awareness about the need for rural service, regional libraries, a national library, and improved library education. The Turgeon Committee afforded an excellent opportunity to give prominence to library matters at the federal government level.

There are a few references to the CLC’s work on 21 June 1944, when a delegation representing 16 national arts groups presented the Reconstruction Committee a brief concerning the cultural aspects of Canadian postwar reconstruction. This “Artists Brief” (as it came to be known) set forth a comprehensive national program to encourage the fine and applied arts and general culture in the interest of an enriched society. It called for establishing a national “governmental body” to administer the arts and for the founding of hundreds of community art and civic centres across the country in municipalities and rural communities, such as the one in Hamilton featured in this accompanying illustration. One component of these centres would be a municipal library in larger cities and regional or county libraries in smaller communities and rural districts. At this time there were only a few libraries operating in community centres. The Dominion government would fund these centres by setting aside $10,000,000. The brief also proposed the coordination of cultural activities by the National Film Board, the National Gallery of Canada, and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation with the building of community centres. Other proposals for government attention concerned many issues such as copyright law, creating a national library, expanding the national archives, and improved programs for federal publications and government information. In the case of library service, establishing a national library in Ottawa would provide for the “circulation of books in Canada and for the sending of the best Canadian books to public libraries in other countries to create a better understanding of Canadian life.” The Arts and Letters Club in Toronto reiterated these ideas and called for “a tremendous extension of library services in Canada.” The playwright, Herman Voaden, one of the artists delegation, said, “When you build a library you make provision for a small stage at one end and for clearing the hall for plays and concerts. You have art exhibitions on the walls.”

At the same June session, the Canadian Authors Association also weighed in on the development of libraries with two specific points:

That travelling libraries be organized and circulated in rural districts throughout Canada, including books written by Canadian authors, and dealing with Canada—these to be drawn from a central library or depot of Canadian books at Ottawa, which shall be adequately financed and staffed for that purpose—the staff to be drawn by preference from discharged Service men or women but strictly limited to competent persons. This library service would fit into the Community Centres Plan accompanying this brief, which we support. That collections of the best Canadian books available be sent to public libraries in other countries of the United Nations, to create a better understanding of Canadian Culture.

Together with other short references, library services caught the attention of Members of Parliament at the June session. In the context of all the cultural briefs, discussions at the Reconstruction Committee hearings, and general postwar planning, CLC forwarded its brief to the Reconstruction Committee in August. The CLC emphasized three critical points at the outset: (p. 5)

The Canadian Library Council believes that an effective, Dominion-wide, library service can make a valuable contribution toward the settlement of post-war problems of rehabilitation by providing books and audio-visual aids in training or re-training demobilized service and civilian personnel for new and old skills; by dispensing current information regarding new developments in the fields of agriculture, industry, business, and the professions; by supplying cultural, recreational, and citizenship reading.

|

London Public Library art display, March1945

|

The Council brief also noted the potential for library development in a national community centres program: “This would be a natural association of services. The Library is open every day to a varied group of readers and its workers are trained in community guidance. The cultural art centre with the library as nucleus (featured in this illustration on the left) has been demonstrated successfully in London, Ontario, where book, art, music, and film services are provided under one administration.” However, the Council advocated a centralized plan of development beginning with a federally appointed and financed national Library Resources Board “to guide, co-ordinate, and encourage provincial, local and special efforts.” The initial focus for the Board would be a survey of existing library resources and book collections used by the armed forces at stations that would be discontinued and any suitable buildings at present used by wartime activities. With this information and collection of provincial data, the Board, using federal funds under its control, could provide incentive grants for regional libraries and devise a system of co-operative use of library resources at provincial and local levels. A regional library would typically be “40,000 people with a budget of $25,000 a year [which is] is the minimum unit recommended in order to supply the readers with the three essentials of library service (apart from buildings accommodation), [that is] a wide range of reading on all subjects, a constant supply of new books, and trained librarians to select the books, advise readers, and manage library affairs.” (p. 8) The National Library Service would include a variety of institutions and ambitious programs:

1) a National Library in a building perhaps dedicated as a war memorial;

2) compilation of a storehouse of national literature and history;

3) development of reference collections on all subjects;

4) formation of a lending collection which other libraries might borrow from when their resources failed;

5) shared microfilm, photostat, and other copying services;

6) a union catalogue to make existing books in libraries available through an inter-library loan on a Dominion-wide basis;

7) the coordination of book information with audio-visual aids, working in close co-operation with the National Film Board, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and other national organizations;

8) administration of collections of books about Canada for exhibition abroad;

9) publication of bibliographical works about Canada.

The Library Resources Board would also encourage adequate standards for personnel, training, salaries, etc. Finally, the Board would provide library consultation services (e.g., legislation, book tariffs, postal rates, the National Selective Service, and functional architectural plans). The proposed national library board to direct and coordinate library work was a bold idea, but it was in keeping with the sweeping powers the federal government had assumed during wartime as well as the central idea proposed in the Artists Brief. Much of the work of the national advisory Library Resources Board could be furthered by assistance from provincial library associations and groups working in adult education or teaching. By providing leadership through the creation of library standards and advisory services, the Library Resources Board could spur library expansion. In this scheme of thinking, a National Library was necessary to implement and support many activities. The CLC’s plan did not avoid the thorny issue of financing by the federal government (p. 10).

Dominion encouragement of library service will need large initial grants. The suggestion has been made that funds could be raised to initiate such projects as library undertakings, community centres, etc., by a special Victory Loan to supply the Tools of Peace. Another suggestion is for an annual per capita tax to provide funds to maintain the above enterprises.

In conjunction with other provincial briefs submitted by library associations and groups, the CLC’s postwar rebuilding vision could advance the nation’s “intelligence, character, economic advancement, and cultural life.” (p. 4) Library reconstruction plans at all government levels would confer benefits for Canada’s citizens and lead to a better, more informed society. Some of the main ideas in the brief— a national commission, a national library, and regionalization—had appeared earlier in January 1944 in Charles Sanderson’s Libraries in the Post War Period. Sanderson had accentuated the potential programs and roles that libraries might assume in their communities and noted the importance of provincial organization. To bolster its case, the CLC appended two more specific documents: Nora Bateson’s Rural Canada Needs Libraries and Elizabeth Dafoe’s A National Library. Both publications had appeared earlier and already received distribution and promotion across Canada. [These will be the subject of future blog posts.]

Like the contemporary Artists Brief, Library Service for Canada achieved little in terms of prompting federal action or securing funding. In the immediate aftermath of WWII, the federal government’s priorities were decidedly not cultural and political support for libraries at local levels sporadic. The arts and library services were provincial and municipal responsibilities. The postwar Liberal governments under Mackenzie King and Louis St. Laurent prioritized economic recovery, jobs and housing for veterans, national defence, and immigration. And there were additional obstacles. Although both the arts and library plans proposed centralized direction and coordination, the building of multi-functional community centres depended on local initiatives and preferences in hundreds of government settings. When Leaside, an independent suburban community in Toronto, decided to build a community centre shortly after the war, the need for sporting facilities, not a library, moved to the fore. As a result, a separate $100,000 library building opened on 8 March 1950 in Millwood Park (now Trace Manes Park), two years before the community centre, which required extensive fundraising beyond original expectations, began operation. The trend to form regional libraries developed slowly. By the early 1950s, there were only two dozen regional or county systems serving about 1,500,000 people in seven provinces, mostly in Ontario. In the realm of education, new schools required increased capital and operating tax levies that made library requests challenging to fulfill. At the national level, federal government enthusiasm for the building of a National Library was episodic. Library advocates began to focus on incremental program activities, not an expensive construction project.

Nevertheless, Library Service for Canada heightened awareness of the need for libraries, especially regional library development and national-provincial planning in a country that had scarcely equated libraries with this type of development before WWII. It presented a progressive vision, parts of which would persist and eventually change Canada’s library landscape for the better.

The ten members representing various Canadian jurisdictions who endorsed the CLC brief were:

Nora Bateson, Nova Scotia Regional Libraries Commission

Alexander Calhoun, Calgary Public Library

Elizabeth Dafoe, University of Manitoba Library

Léo-Paul Desrosiers, Montréal Public Library

Hélène Grenier, Bibliothèque des Instituteurs de la Commission des Ecoles Catholiques de Montréal

Gerhard R. Lomer, McGill University Library

John M. Lothian, University of Saskatchewan Library

Edgar S. Robinson, Vancouver Public Library

Charles R. Sanderson, Toronto Public Library

Margaret S. Gill, Chairman, National Research Council Library, Ottawa

Further reading:

Canadian and Newfoundland Education Association. Report of the Survey Committee Appointed to Ascertain the Chief Educational Needs in the Dominion of Canada (Ottawa: the Association, March 30th, 1943).

Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Special Committee on Reconstruction and Re-establishment. Minutes and Proceedings of Evidence, vol. 1. Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1944.

Nora Bateson. Rural Canada Needs Libraries. Ottawa: Canadian Library Council, 1944. [Previously, a shorter version had appeared as an article: “Libraries for Today and Tomorrow,” Food for Thought 3, no. 5 (February 1943): 12–19.]

Elizabeth Dafoe. “A National Library,” Food for Thought 4, no. 8 (May 1944): 4–8.

Library Service for Canada was republished along with accompanying provincial briefs in 1945. This book, Canada Needs Libraries, was reviewed previously in 2017.