|

| Brantford Public Library in 1917 |

Andrew Carnegie promised Brantford $30,000 after receiving a 1902 request from a prominent local judge, Alexander David Hardy, who was deeply interested in books, libraries, history, and cultural life in the city. Judge Hardy became an active local library trustee who later served as President of the Ontario Library Association in 1909—10. Brantford was one of Ontario’s leading cities at the time, with a population (1901 census) of just over 16,000. In a contemporary 1902 report by Lawrence Burpee, “Modern Public Libraries and their Methods,” Brantford reported holdings of almost 17,000 volumes and circulation just short of 67,000 items per year. The library staff numbered four, and a printed catalogue recorded holdings. About eighty percent of the collection was classed as fiction. This figure may reflect that the library used an antiquated classification system initially designed for mechanics’ institutes in Ontario thirty years earlier. More proficient methods were about to be employed under a new librarian, Edwin D. Henwood, including the Dewey Decimal system. Henwood became one of the many Ontario voices for improved library service in the course of his twenty-two years as chief librarian. He died suddenly in 1924 leaving a bequest of $1,000 for the children’s section that he had introduced.

After the city council agreed to comply with Carnegie’s terms to support its new free library, during the construction phase, costs escalated well beyond original 1902 estimates. Again, Hardy wrote to the Scottish-American philanthropist, who responded with an additional $5,000 in 1904 to complete the city’s building on the main square. As years passed, Hardy remained fully engaged with the library’s development, and in 1913, when the need for an enlarged stack room and basement became evident, he again asked for increased funding. Fortunately, the Carnegie Foundation (est. 1905) granted $13,000 of the $15,000 required to make the new renovation possible. The three grants totalling $48,000 became one of the most significant for Carnegie library buildings in Canada.

Many different exterior architectural elements exhibited the Beaux-Arts symmetry and style of the library. These features are evident in a serious of pictures taken by the award winning Park Co. [Edward P. Park] that are preserved at the Archives of Ontario.The Beaux-Arts style was popular in Europe and North American and suited more refined cultural tastes and respect for literature and reading. The classical form included a large portico supported by four Ionic columns surmounted by a triangular pediment. The dome above the portico offered an impressive visual presence which was complemented by a hipped roof. “Public Library” was inscribed across the nomenclature beneath the pediment, and just below above the main entrance, a Latin verse from the Odes of Horace proclaimed, “I have erected a monument more lasting than bronze.” To some people, the library exuded a sense of permanence--it was a lasting storehouse of knowledge. The exterior classical form of the building also included smaller formal decorations. Three small palmettes (arcoteria) adorned the two sides and peak of the central pediment. The names of famous Anglo-American writers such as Shakespeare, Tennyson, Emerson, Dickens, Burns, and Thackeray were engraved on the smaller pedimented main-storey front windows.

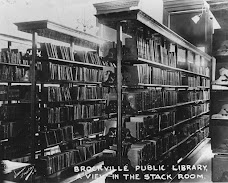

Inside the library, the primary visual feature at the entrance was, of course, the rotunda under the dome. Several stained-glass skylights at the top gave an air of elegance and permitted more highlighting of the recessed displays, marble walls, mosaic tiled floor, and adjoining rooms. The two separate reading rooms (each 884 sq. ft.) flanking the rotunda were designed separately for ladies and gentlemen. The stack room (1,560 sq ft.) was located at the back and fronted by a charging station with two smaller rooms to each side (each 300 sq. ft), one for reference another for the librarian. There was no direct public access to the bookshelves, and the library enforced an age limit of fourteen which barred children. Stairs to the lower level led to a men’s smoking and conversation room (35 ft x 25 ft), a lecture room (35 ft x 25 ft), and a board room for meetings.