D’obscurantisme et de Lumières: La Bibliothèque Publique au Québec, des Origines au 21e Siècle by François Séguin. Montréal: Éditions Hurtubise (Cahiers du Québec, no. 168), 2016.

The presence of libraries in Quebec stretches back almost four centuries; their history is complex and  plentiful. Now, François Séguin has composed a comprehensive and noteworthy history of libraries used by the public on various terms from the 18th to the 21st century. The author worked for many years in Montreal’s public libraries and has witnessed firsthand the developments over the last forty years. As a historical work, the focus is primarily on the era before 1950; the progress made after the Quiet Revolution is dealt with more briefly. The title reveals the fundamental theme of enlightened progress impeded by conservative elements opposed to the democratization of library access to public reading and knowledge. The author explores why predominantly French-speaking Quebec has undergone an ideological/political library struggle that was not present in other Canadian regions. Yet, there are similarities with English-speaking counterparts: like other North American library developments, the manifestations of the “public library” in Quebec has passed through periods of private, semi-private, and tax-supported services that ranged from the exclusionary use of shareholder/subscribers to municipal entities usually free to local/regional residents. It is this eventful passage that will fascinate many readers.

plentiful. Now, François Séguin has composed a comprehensive and noteworthy history of libraries used by the public on various terms from the 18th to the 21st century. The author worked for many years in Montreal’s public libraries and has witnessed firsthand the developments over the last forty years. As a historical work, the focus is primarily on the era before 1950; the progress made after the Quiet Revolution is dealt with more briefly. The title reveals the fundamental theme of enlightened progress impeded by conservative elements opposed to the democratization of library access to public reading and knowledge. The author explores why predominantly French-speaking Quebec has undergone an ideological/political library struggle that was not present in other Canadian regions. Yet, there are similarities with English-speaking counterparts: like other North American library developments, the manifestations of the “public library” in Quebec has passed through periods of private, semi-private, and tax-supported services that ranged from the exclusionary use of shareholder/subscribers to municipal entities usually free to local/regional residents. It is this eventful passage that will fascinate many readers.

A summary of the book’s twelve chapters must, of course, not do justice to the depth of Séguin’s scholarship and his ability to provide an appealing narrative based on the history of individual libraries. An introductory chapter briefly outlines private and institutional libraries in New France before the British conquest in 1760. The establishment in 1632 of the Bibliothèque du Collège des Jésuites was a significant highlight of the French regime, but it was not for public use. The concept of public use and literacy growth was demonstrated by the establishment of small subscription libraries, commercial lending libraries, reading rooms, newsrooms, and mechanics’ institutes (instituts d’artisans) in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The appeal of these organizations to different clienteles is outlined in the following three chapters, 2 to 4. These libraries were utilized mainly by urban elites, professionals, and people engaged in business. Before the province of Lower Canada was united with Upper Canada to form one British colony in 1841, the major points of interest were:

1764 — Germain Langlois forms a commercial circulating library at Quebec;

1779 — British Governor Haldimand founds the bilingual Bibliothèque de Québec/The Quebec Library;

1828 — The establishment of Mechanics’ Institute of Montreal (now the Atwater Library).

At this point, 1841-42, an extraordinary French visitor from the United States, Alexandre Vattemare, an exponent of free public libraries and the universal distribution of reading through exchanges of books, arrived (chapter 5). In Montreal and Quebec, he proposed the union of local societies into one institute that would form a library, museum, and exhibition halls bolstered by his exchange plan. Séguin devotes an entire chapter to his efforts which did not materialize but ultimately led to the formation of the Institut Canadien in 1844 in Montreal. The intellectual ferment of the early 1840s also stimulated a response from conservatives anxious to block liberal, secular ideas that might threaten the conservative elite and the Catholic Church’s authority. Two chapters (6 and 7) explain the problems encountered by the Institutes Canadiennes in Montreal and Quebec and the development of the parish library (bibliothèque paroissiale) by Catholic authorities. For a century to come, the parish libraries were open for readers, but their organizers placed priority on a rigid system of morality that taught acceptance and passivity in social and political matters. Orthodoxy was more important than the liberal sponsorship of public lectures, debates, and circulating collections that the institutes promoted. The opening of the “Œuvre des Bons Livres” in Montreal by the Sulpician Order in 1842 signalled decades of conflict between the two philosophies while the church succeeded in establishing its hegemony over public reading and defeating the philosophy of the two institutes. The Catholic hierarchy was determined to stiffle the influence of “bad books” by providing “good” ones.

After Confederation in 1867, the Sulpicians began to play an important role in championing publicly authorized reading (chapter 8), notwithstanding the proclamation of an 1890 provincial Act (seldom used) that authorized municipal corporations to maintain public libraries. When Montreal’s civic authorities failed to secure funding from Andrew Carnegie to establish a public library, the Sulpicians founded the famous Bibliothèque Saint-Sulpice for the public and scholars. Eventually, in 1967, its collections became part of the Bibliothèque nationale du Québec and later, after 2002, the provincial government integrated its resources with the Grande Bibliothèque, one of the busiest public libraries in Canada. The formation of the “GB” owed much to the sponsorship of Lucien Bouchard, the leader of the Premier of Quebec between 1996-2001. This chapter of D’obscurantisme et de Lumières underscores the author’s general theme and how social and political elements impact public library development.

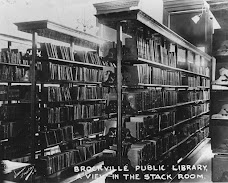

The Saint-Suplice Library was a remarkable beaux-arts style building, but it was followed shortly afterwards by an equally imposing edifice in the same architectural style, the Bibliothèque municipale de Montréal, which opened in 1917. By the turn of the twentieth century, there were gradual social, economic, and political forces underway that would eventually undermine the dominance of the parish library in local communities as well as the authority of the clergy in determining collection building. English-speaking minorities, especially in major urban centres and the Eastern Townships, evoked the rhetoric of the Anglo-American public library movement, which embraced municipal control and free access at the entry point for public libraries. Séguin charts the course of this inexorable movement in three chapters, 9 to 11. In Montreal, the Fraser Institute, Quebec’s first free library for the public, opened in 1885, followed by anglophone public libraries in Sherbrooke, Knowlton, and Haskell. Westmount opened another free library in 1899. Even a small francophone municipality, Sainte-Cunégonde, founded a free library immediately before Montreal annexed it in 1905. However, Montreal’s municipal public library on Sherbrooke Street grew slowly because financial resources from the city for collections and staffing were in short supply during its first half-century of existence. Children’s work and a film service were not introduced until a quarter-century after the library opened. After the Second World War, the forces of urbanization, secularization, and the unique national identity of Quebec began to change the province’s political culture and introduced a new important player in public library development--the provincial government.

The book’s final chapter (11) deals with the growth of public libraries after 1959 when the province passed a modest provincial law for public libraries authorizing municipal establishment and control of library services. Regional libraries were planned and formed, professional staffing was encouraged, improved revenues from local government were secured, new branch libraries opened, and new library associations formed that emphasized social issues, such as intellectual freedom. In the early 1980s, Denis Vaugeois, the Minister of Cultural Affairs, emphasized library development with a five-year development plan that improved infrastructure and services substantially. Yet, when the province rescinded the outdated 1959 library legislation, no new specific library act was enacted. Instead, the province moved to establish the Grande Bibliotheque in Montreal, an outstanding circulating and reference library for all Québécois. However, lacking a general law, basic principles, especially free access to resources, remains a legacy of flawed, incremental plans . The current general legislation, one concerning the Ministry of Culture and Communications, has governed public libraries since 1992. Séguin entitles his chapter on the twentieth century “un laborieux cheminement,” an appropriate designation.

D’obscurantisme et de Lumières is a rich narrative firmly focused on the institutional development of libraries and their public value in terms of access to books, the intellectual or recreational content of collections, and a broad range of formats that have challenged the dominance of print after the first decades of the 20th century and the popularity of radio. Séguin uses many documentary sources to illustrate his chapters: quotes from bishops, politicians, and librarians; newspapers such as Le Devoir; personal correspondence; municipal debates; government reports; and, of course, library reports. Influential American practices, such as the Dewey Decimal Classification and the evolution of library science education in degree-granting universities, are evident. But several decisive post-1950 changes are not in evidence. There is little in the book about societal changes, for example, the transformation to electronic-virtual-digital libraries, the “Information Highway” of the 1990s, gender roles (especially the predominance of males in administration), the image of the library or librarians in films or television that reflected societal views, or the effects of library automation and efforts to network libraries for collective usage. Perhaps a few in-depth case studies of major libraries outside Montreal might have been used to illustrate library progress. For example: more emphasis on how the Institut Canadien de Québec, which initially accepted the church’s authority on morality and orthodoxy, then evolved in a singular way into Quebec City’s public library after municipal control in 1887; or, how the regionalization of rural library service proceeded after 1960. The use of informative sidebars on Montreal’s two library schools, influential librarians (e.g., Ægidius Fauteux), children’s libraries, or library associations such as ASTED or the l'Association des bibliothécaires du Québec/Quebec Library Association could advance our knowledge of library progress.

However, these observations in no way diminish the significance of D’obscurantisme et de Lumières as it stands. François Séguin has made a valuable contribution to Canadian library history and allows his readership to understand better the cultural forces that determined library development and the course of librarianship in Quebec. The issues I pose simply suggest that a second book by the author employing various contemporary themes would be equally helpful for those eager to know more about Quebec’s remarkable library history.