Canadian Carnegie Grants for Public Libraries

At the turn of the 20th century, the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie rapidly became an internationally recognized supporter of public libraries in Anglo-Saxon countries. In Canada, in the period 1901–22, 125 buildings were erected as libraries using grants promised by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The terms for receiving a grant directly from Carnegie personally or the Carnegie Corporation before the grant period ended in 1917 were straightforward. After a community representative(s) outlined the need for a public library and a promise of funding was secured, two commitments were required from local municipalities before funds for a building were released: a suitable site and a promise to provide at least ten percent of the total grant for annual operating expenses. There were also two further requirements, one that boosted the social standing of public library service: the library must be free to its citizens at the point of entry and, from 1908 onward, applicants had to submit building plans for final approval before receiving funds. Most architectural arrangements were made locally. Carnegie and his personal secretary, James Bertram, who managed most of the library correspondence, often insisted on dealing with elected officials and library trustees. The standard Carnegie formula for awarding grants was approximately two dollars per capita.

There are many books, articles, and internet sources of information on the Carnegie program in Canada. A standard printed reference is the 1984 work by Margaret Beckman, Stephen Langmead, and John Black, The Best Gift: A Record of the Carnegie Libraries in Ontario published in Toronto by Dundurn Press. However, there were some communities — thirty-one in all — that sought and received a promise of Carnegie funds to build a library which never reached the construction stage. These communities eventually saw their opportunity lapse. There were many reasons why these communities lost the chance to build a library with the promised funding:

— people were not convinced that a public library was necessary;

— a few municipalities officially declined the Carnegie offer;

— there was opposition to increasing the annual tax burden, that is 10% of the promised grant;

— the requirement to pass a bylaw to create a free library was not achieved;

— local communities were unable to secure a suitable site;

— the requirement that it be purpose built as a library became objectionable;

— after 1908 building plans had to be approved by James Bertram and he rejected some because they were too ornate or featured non-library space for features such as museums or offices;

— many people, including organized labour, objected to ‘tainted’ or ‘blood’ money given Carnegie’s controversial record in suppressing the Pennsylvania Homestead Strike in 1892;

— anti-American attitudes despite Carnegie’s enthusiasm for Anglo-Saxon community governance;

— some communities requested additional or reduced funds that were not approved Bertram;

— local apathy or confusion about the stipulations of the grant promise.

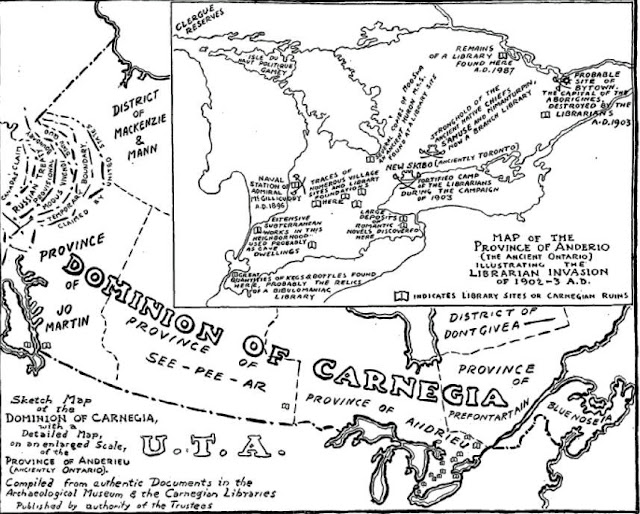

The acceptance of a Carnegie grant was often controversial and subject to many comments in the contemporary press, such as humorous graphic printed in Toronto by The Moon on February 21, 1903.

Lapsed Carnegie Library Grants in Canada 1901–18

Because Carnegie was viewed as a foreign figure or as an ardent capitalist, many writers have assumed that lapsed or refused grants were motivated by a desire to avoid associating with Carnegie and creating memorials to his name. But again, a few case studies reveal the complexity of involvement with the Carnegie library program. The largest grant, $150,000 to Montréal, ground to a halt in 1903 after formidable opposition from the Catholic Archbishop, censorship concerns, and the linguistic divide in the city. In Ontario, Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay) received three promises: a grant of $10,000 in 1902, an increase to $30,000 in 1909, and then an additional $10,000 in 1910. Despite some delays with building plans, the city was ready to erect a $40,000 building by early 1912. However, Bertram reduced the grant by $10,000 in March 1912 because revised 1911 population census figures indicated fewer people than the official application, which was based on municipal assessment. As a result, everything collapsed; the library board and council preferred a larger building and the project was lost. Halifax declined its $75,000 offer after it was unable to get a suitable site and became embroiled in a legal battle about its authority to accept. St. John’s $50,000 promise lapsed after its building proposal included museum and offices which did not receive approval. Saskatoon, a relatively new city in a new province, decided not to proceed with its $30,000 offer after its request to raise the amount to $75,000 in July 1912 due to building costs was turned down by Bertram.

Smaller places were usually in a more precarious financial state, especially in Ontario. Tilbury’s original $5,000 grant, approved before the WW I, was rescinded by the Carnegie Corporation in the mid-1920s. The entire project was beset by a series of false starts at the tendering stage, a reluctance to submit a free library bylaw to the electors, requests for additional money, delays because of municipal funding problems, a prohibitive rise in costs, and bitter local rivalry over site selection. Otterville, a police village situated within the Oxford County, was considered by Bertram to be too small for a grant; instead, he promised $6,000 to the township of South Norwich in March 1915. Special legislation permitting townships to form boards was duly arranged by the province in 1916, but the war effort scuttled any further movement in this direction until January 1923, when township electors refused to pass a free bylaw. Consequently, the award to South Norwich lapsed. Trenton received a promise for $10,000 in April 1911 and passed its free bylaw; however, when local library efforts flagged the provincial library Inspector, Walter Nursey, rescinded its free status in 1913, and Bertram judged the endeavour finished. Efforts to revive the Trenton pledge after WW I failed. Bertram testily advised that its revised proposal to construct a library as a war memorial should be financed by a local community, not an “outside agency.” Caledonia’s $6,000 promise lapsed because its free status was revoked when it failed to comply with provincial regulations. Thessalon, which received a $8,000 promise, requested a smaller amount since representatives felt that $500 (not $800) per annum was sufficient for its library. Similarly, Neepawa (Manitoba) assessed that it could not commit to the ten percent annual tax expenditure and asked for a reduced promise: Bertram refused based on his knowledge that $600/year was already the bare minimum needed for adequate service.

Eventually, the communities that experienced problems with Carnegie funding did build public libraries at their own expense. The library story did not end because library advocates continued to press for better services. Larger cities, such as Halifax and Montréal, now boast prominent central library faculties. Smaller communities are part of larger municipal or regional systems. For the most part, the history of their lapsed grants remain to be told in more detail because attention has been focused on the architecture and stories of successful Carnegie promises. A listing of lapsed Canadian grants follows:

| Province | Community |

Promise in $$$ | Date of Award |

| Alberta | Raymond | 10,000 | December 24, 1909 |

| Manitoba | Neepawa | 6,000 | January 8, 1908 |

| Manitoba | Brandon | 36,000 | July 9, 1913 |

| Newfoundland | St. John's | 50,000 | June 21, 1901 |

| Nova Scotia | Amherst | 5,000 | February 6, 1907 |

| Nova Scotia | *Halifax* | 75,000 | February 4, 1902 |

| Nova Scotia | Yarmouth | 4,000 | October 3, 1901 |

| Nova Scotia | Truro | 10,000 | October 4, 1902 |

| Nova Scotia | Sydney | 15,000 | March 8, 1901 |

| Ontario | Arthur | 7,500 | March 13, 1909 |

| Ontario | Beeton | 5,000 | May 16, 1911 |

| Ontario | Chesley | 10,000 | January 6, 1912 |

| Ontario | Merrickville | 2,500 | April 8, 1907 |

| Ontario | Milton | 5,000 | January 29, 1906 |

| Ontario | Newmarket | 10,000 | March 29, 1911 |

| Ontario | Paisley | 5,000 | January 8, 1908 |

| Ontario | Petrolia | 10,000 | December 13, 1907 |

| Ontario | Strathroy | 7,500 | March 21, 1908 |

| Ontario | Thessalon | 8,000 | August 28, 1908 |

| Ontario | *Port Arthur* | 10,000 | April 11, 1902 |

| Ontario | Port Arthur | increased 30,000 | February 1, 1909 |

| Ontario | Port Arthur |

increased 10,000 | April 16, 1910 |

| Ontario | Port Arthur |

reduced 10,000 | March 18, 1912 |

| Ontario | Trenton | 10,000 | April 8, 1911 |

| Ontario | Gananoque | 10,000 | August 11, 1911 |

| Ontario | Otterville | 6,000 | March 16, 1915 |

| Ontario | Caledonia | 6,000 | December 8, 1913 |

| Ontario | Millbrook | 8,000 | December 8, 1913 |

| Ontario | Tilbury | 5,000 | July 23, 1914 |

| Ontario | Tilbury |

increased 2,000 | March 11, 1918 |

| Québec | Montréal | 150,000 | July 23, 1901 |

| Québec | Sherbrooke | 15,000 | February 4, 1902 |

| Québec | Trois-Rivières | 10,000 | April 11, 1902 |

| Saskatchewan | Saskatoon | 30,000 | May 16, 1911 |

| Saskatchewan | Indian Head | 10,000 | May 8, 1908 |

* the 1902 Port Arthur promise was rescinded and replaced in 1909–10. The promise to Halifax was increased from $50,000 to $75,000.

My two earlier blogs on Carnegie libraries are on the Brantford Library constructed in 1904 and the Brockville Library opened in 1904.

My blog on William Austin Mahoney, who was the architect for many Carnegie libraries in Ontario is at this link.