William Austin Mahoney: A Prolific Canadian Carnegie Library Architect

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Andrew Carnegie began dispensing grants to Ontario libraries. Many ambitious cities and towns submitted a request for assistance. One important requisite that Carnegie demanded was that the library be “free” that is, open at the point of entry free of charge—there would no longer be a subscription for membership. This condition would make it eligible for a specific amount from its municipality according to Ontario’s public library legislation. More than a hundred communities followed through and received grants.

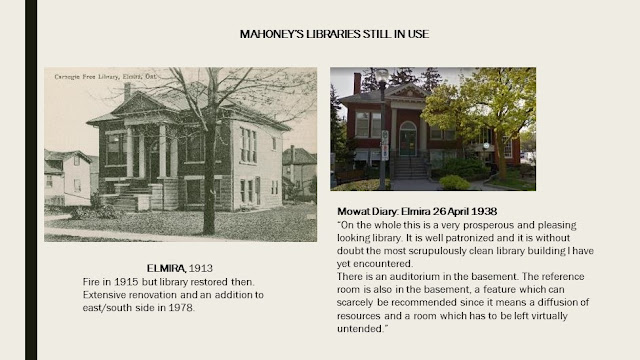

One architect from Guelph, Ontario, William A. Mahoney (born 16 Sept. 1872 and died 13 Oct. 1952) designed fifteen buildings across the province. This short history looks at Mahoney’s buildings and their subsequent development until the period of the Second World War, especially in connection with Angus Mowat, who inspected most of Mahoney’s buildings and reported on their status about a quarter-century after they originally opened. There were examples of progressive and struggling libraries in Mahoney’s grouping prior to 1945.

William Mahoney’s contribution to the Carnegie architectural history of Canadian libraries was large in number but small in terms of interior design and exterior features. His preference for simple, square, classical buildings with raised first floors requiring staired entrances, and open floor plans suited the building period and size of grants that the Carnegie corporation favoured for smaller towns across Canada, especially in Ontario. For his exteriors he followed the neoclassical style associated with the École des Beaux Arts in Paris which was in vogue across North America when he opened his office in Guelph. There were two basic exterior types of neoclassical style: a columned temple entrance with a triangular pedimented roof or a columned arch entrance divided into one or more bays which supported the roof line. In the interiors there were high ceilings, wooden shelving and chairs, oak floors, stained glass in a few windows, busts of famous literary figures, and fireplaces along with radiators to provide heating. Separate reading rooms for women and men were not uncommon. Spacing and reading for children for limited.

For the most part, Mahoney’s ideas were in accord with changing principles for library buildings. In the leaflet published in 1910, Notes on the Erection of Library B[u]ildings, James Bertram, the secretary of the Carnegie Corporation, introduced the open library concept wishing to receive a promise of funding. The Notes were intended for buildings in small communities or city branches. Bertram stressed simplicity: rectangular, one-storey buildings, undivided rooms, low ceilings, few restrictions separating readers from books, and unpretentious exteriors. Bertram personally inspected potential designs for libraries before authorizing funding. Fortunately, Mahoney’s plans usually passed muster. Mahoney continued a successful practice, building schools and commercial buildings for many years until his retirement. Seven of his buildings continue in use as libraries in 2023.

A testament to Mahoney's design concepts came from Angus Mowat, the Ontario Inspector of Public Libraries from 1937 to 1960, about thirty years after the libraries opened. The Inspector found most of Mahoney's libraries were still generally community assets, although crowded and in need of extensions or interior reorganization. One suggestion, used in a number of Carnegie buildings in the following decades, was to house children's sections in basement rooms that had being planned for other uses. Another testament to William Mahoneys success as an architect is that many of his buildings remain in use more than a century after their construction, surely a notable achievement.

My PowerPoint presentation was originally planned for the Port Hope Public Library in 2023, but due to illness I was unable to attend and I have reproduced it here in JPEG format.

A complete listing of William Mahoney’s buildings is at the website, Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800–1950.

Some of my earlier blogs on Carnegie library buildings:

Photo Essay on Ontario's Edwardian Libraries (1989)

More Carnegie library buildings in Ontario are available at my previous website, Libraries Today, from the 1990s — The Ontario Library Photo Gallery — stored on the Wayback Machine of the Internet Archive.

My chapter on Carnegie Philanthropy (pp. 165–203) appears in Free Books for All: The Public Library Movement in Ontario, 1850–1930 (1994) which is available on the Internet Archive.

Comments

Post a Comment

Leave a comment