One Place to Look; The Ontario Public Library Strategic Plan. Prepared by the Ontario Public Library Strategic Planning Group. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Culture and Communications, 1990. 68 p., illus. Also published in French with title: Une voie d'accès à l'information.

By the start of the 1990s, public-sector strategic planning meant the development of a mission statement, a more complete analysis of the factors influencing library service, specific recommendations about goals, long-term objectives to achieve these goals, and recommendations for implementing the new vision. An inclusive method could lead to agreement about principal services and structures. By mid-1988, a small planning group chaired by Elizabeth Hoffman, a founding member of the Association of Canadian College and University Ombudsmen and a Toronto Public Library trustee, came together to plot Ontario’s first strategic plan for library service. For many years, librarians and trustees had looked to briefs, regulations, and legislative provisions to define the library’s role and functions. Now, legislative provisions were not to be the outcome. Now, planners had to submit convincing recommendations to many partners and hope for a successful implementation process on the part of many libraries across the province—large or small!

An Ontario Public Library Strategic Planning Group (SPG) began its process in March 1988, forming teams to prepare reports, such as technology, and developing a mission statement that later became a Statement of Purpose. Elizabeth Cummings for the Libraries and Community Information Branch (LCIB) and Margaret Andrewes for the OLA maintained a communication plan and helped coordinate the work of the SPG to support its deliberations. For months, the SPG attended meetings to outline the process and collate information on areas of fundamental interest, such as service to northern Ontario, equity of access, education for staff, technology, or funding. The task groups studied and analyzed major issues, and by summer 1990, the SPG was ready to finalize its drafts after receiving more than two hundred briefs and presentations at local public hearings. A final document, One Place to Look, was released in time for the November 1990 OLA Toronto conference. At this convention, there was some optimism about the organization’s strategic document. So, plans were commenced to form a consensus and implement as many SPG recommendations as possible. All stakeholders, i.e., the provincial government, municipal councils, library boards, and library users, needed to be proactive in developing their strategy for implementing One Place to Look in their community.

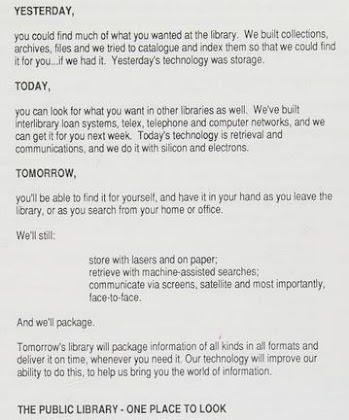

One Place to Look was a progressive vision that sought to situate libraries on “the crest of the information wave” that was beginning to sweep the globe. In 1989, the National Science Foundation’s NSFNET in the United States had gone online, and in the following year, Tim Berners-Lee, a scientist at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, unveiled the Hypertext Markup Language (HTML). In 1991, CERN introduced the World Wide Web and the number of websites began to proliferate. The development of Netscape Navigator, Yahoo!, and a Microsoft browser for Windows 95 quickly followed. The ‘electronic library’ would soon give way to the ‘digital library.’

Nevertheless, several themes in One Place to Look were familiar. The mantra of “access to the right information at the right time” harked back to an earlier 20th-century motto about books: “the right book for the right reader.” The cornerstones for progress would be:

(1) equitable access to information; (2) helping people find the right information; (3) provision of materials for pleasure and relaxation; (4) free access to resources; and (5) the library as a lifelong educational agency (p. 13). Four goals were to achieve these societal purposes, each with basic objectives and several recommendations. It was a plan with a purpose, ways and means to get there, and a collaborative approach that would give all participants a common purpose and direction. Its four fundamental goals were:

1. Every Ontarian will have access to the information resources within the province through an integrated system of partnerships among all types of information providers;

2. Every Ontarian will receive public library service that is accurate, timely, and responsive to individual and community needs;

3. Every Ontarian will receive public library service that meets recognized levels of excellence from trained and service-oriented staff governed by responsible trustees;

4. Every Ontarian will have access to the resources and services of all public libraries without barriers or charges.

Detailed objectives were the key to the entire strategic planning process because they linked goals with outcomes. There were twenty objectives, which were grouped around several major concerns:

—development of an information policy and strategy for Ontario;

— an integrated, province-wide public library information network;

— promotion of effective units of service;

— effective, electronic access to all collections in the province-wide network;

— a program to preserve printed and electronic information;

— programs to encourage innovation and removal of barriers to service;

— an education program for trustees to provide leadership;

— development of staff expertise;

— removal of barriers to service due to “race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, age, marital status, family status, or handicap;”

— equity of access to service for all Ontarians, regardless of geography;

— public library service and access to the provincial network for all Ontarians without charge;

— funding to support the integrated, province-wide public library information network.

One Place to Look was an inspired visionary document. At a time when a 1989 Gallup Canada Survey revealed that only 43% of the people it interviewed were aware that they could phone the public library for information, the SPG was saying that people would be able to access materials in their libraries from the comfort of their homes. For many people, the futuristic vision was difficult to square with current conditions. Unfortunately, the strategic plan was rolled out just as North America entered a major recession that ravaged Ontario between 1990–92. Government revenue at all levels shrank; consequently, hard choices were made, and cutback management became more important. Although the MCC announced in early 1991 that its funding for libraries would not be cut and that money for Indian Bands and libraries would be increased, government per capital library revenue peaked in 1992 and remained flat for another three years. At the same time, some library services, such as reference and circulation, continued to grow.

Financial considerations came to the fore because revenue was stagnant; thus, library boards and CEOs seriously investigated other sources, such as budget trimming and user fees. Deliberations on strategic planning were also lessened by the rapid development of the Information Highway and the need for libraries to develop Internet services and expend more on technological considerations. One Place to Look required two critical structures for successful implementation: first, a central provincial office to coordinate and manage an integrated provincial network; second, a Strategic Planning Council with representation from all library organizations to advise and recommend policy to the coordinating body based on an agreement in the broader community. However, provincial governments for decades had been unenthusiastic about establishing a central coordinating body to provide province-wide administration for library services. The two 1990s provincial OLS agencies (South and North) were a means, not formal agencies, to carry out liaison, coordination, and advisory services across the province. Generally, the period 1991–95 was punctuated by cabinet shuffles and ministry realignments; consequently, there were few opportunities to prioritize libraries or expand the Libraries and Community Information Branch’s (LCIB) role. From its reorganization in the late 1970s, the LCIB (especially under Wil Vanderelst) had actively promoted coordination among Ontario library boards and had worked to improve their efficiency. In 1993, the LCIB did publish a short statement, One Place to Look: Ontario Public Library Strategic Plan, 1990: 3 Years Later, without much fanfare. As well, work towards formation of Network 2000, an an effort to connect Ontarians to the global information highway through their public libraries, had commenced. However, in 1995, the LCIB was reformed into a new Ministry and its functions merged with a new, broader-focused Cultural Partnerships Branch.

For strategic planners, the recession, the lack of government continuity, plus the absence of a major coordinating body at the provincial level were major impediments. One promising development was the creation of an Ontario Public Libraries Strategic Directions Council (SDC) in 1992 that began working on marketing, telecommunications, and revision of the strategic plan. This group consisted of representatives from all library sectors: all public libraries; the OLS and LCIB; Metro Toronto Library; and the OLA. As a practical consideration, additional project money for a second-generation network, INFO, the Information Network for Ontario, was put into place in 1992 by the MCC to create a provincial database for distribution on cd-roms. INFO could then connect with a regional high-speed network, ONet, to become part of a larger publicly accessible enterprise. Later, in February 996, the SDC released a short discussion paper: A Call to Action: Specific Initiatives to Advance Public Library Development in Ontario, but it failed to generate sufficient attention during the ‘Common Sense Revolution’ turbulence unleashed by the Progressive Conservative government.

During this period, the OLA emerged as the biggest booster of library strategic planning. At OLA’s 1991 conference, a new division, the Ontario Library and Information Technology Association (OLITA), was created to address the impact of the burgeoning Information Society. In May 1992, OLA published A Proposal for an Information Policy for Ontario which updated a report from the 1989 exercise leading to One Place to Look. To interest small libraries under 10,000 in strategic planning, OLA’s conferences in 1991 and 1992 featured “The Hometown Library” mini-conference sessions for trustees and staff. To raise information awareness and sustain One Place to Look, OLITA began to promote interdisciplinary exchanges, research, standards, monitoring of new technologies, and development of models for library systems and networks. In 1992, it joined with the ALA to sponsor a series of meetings on international technology, “Ten Days to 2000,” which heightened consciousness about networking, the Information Highway or the Internet. In the following year, 1993, OLA formed the Coalition for Public Information with representatives outside libraries as a voice for public participation in the emerging telecommunications-information field. Partnerships like the Coalition represented one of the objectives the Strategic Planning Group had recommended to broaden the action base on important issues. Thus, on some fronts, the strategic planning process was progressing despite challenging economic conditions.

Nonetheless, the effects of the recession hampered OLA’s ability to promote libraries at a crucial time. Public sector realignments exposed libraries and librarianship to the rationalization of work and technological expertise in an increasingly unionized workplace and magnified the weaker form of tiered library governance (province-municipality-board) and multiple professional and trustee associations. For a time, OLA was coping with declining membership and finances. Staffing levels for librarians and technicians had moderated after the Bassnett Report in the early 1980s, and there was little flexibility in personnel budgets. One Place to Look continued to be a rallying cry into the early 2000s. Many of its objectives were a work in progress for many years: improved guidelines for smaller libraries, certification programs and better training for staffing, more effective electronic access, a program to preserve printed and born-digital information, and other worthy activities. For the most part, the strategic plan was eventually a successful endeavour and a model for future library planners. References to it still appear in library publications, and the catchy phrase, ‘One Place to Look,’ continues to reverberate in library language, in many ways supplanting older library mottos that emphasized reading and books.

One Place to Look has been digitized and is available for viewing on the Internet Archive.

My earlier 2022 blog on the Bassnett Report is also available for viewing.